Keeping it Simple

Calling the degree requirements and transfer procedures at California community colleges “complex to navigate,” Assistant Professor Rachel Baker is working to simplify things.

|

In 1994, the California state senate passed SB 1914, establishing a program that allows students enrolled in any campus of the California Community Colleges to enroll, without formal admission, in a maximum of one class per term at any CSU or UC campus.

The program, known as “Cross-Enrollment,” has noble aims – to expose students, particularly underserved students, to the community and academics of a four-year university. By doing so, students become familiar with faculty, classmates, and the campus. Such experiences could make it easier for students to eventually transfer to one of the state’s public universities. Assistant Professor Rachel Baker recently discovered the program is not as popular as one might expect. Approximately 150 students have cross-enrolled from the California Community Colleges System to UCI over the past five years, a paltry number when considering the immensity of the California Community Colleges System. |

“There are more than 250,000 community college students within a 20-minute drive of UCI, and a majority of them enroll with the intention of transferring to a four-year institution,” Baker said. “It’s important we figure out why this program hasn’t been utilized to the extent it could be and how we might make it more popular among students. Increasing participation in Cross-Enrollment might lead to better educational and career outcomes for thousands of students.”

With a five-year, $2.5 million grant from the National Science Foundation, Baker is doing just that. This past year, the first of the grant, Baker and Loris Fagioli, director of research at Irvine Valley College, along with a team of undergraduate students, doctoral students, and postdoctoral scholars, conducted 12 focus groups with students and counselors at Orange Coast College, Irvine Valley College, and Saddleback College.

Their preliminary findings revealed that roughly 90 percent of students were unfamiliar with the Cross-Enrollment program. Once learning about it, their interest piqued, but concerns about assimilating, transportation costs, and access to tutoring and library services pervaded.

As did the question of what classes to take, for a few reasons. First, degree requirements are complex and it is difficult to determine which classes can be used to fulfill specific requirements. Second, many students noted that the smaller class sizes and accessible instructors at their community college were what initially attracted them to the school; students were worried that taking a difficult class in an unfamiliar setting might harm their GPA and, ironically, lower their chance of successfully transferring.

Now that Baker has discovered these concerns, she and her project team are establishing an intervention that will provide a range of services to groups of community college students at the partner campuses. For example, one group of students will simply receive information about the program. Another group might receive information and a parking stipend. Yet another might receive information, parking, assistance in filling out the required paperwork, and guidance on selecting which class to enroll in.

Baker and her team will then follow the students for five years to see what helps increase the rate of participation in the Cross-Enrollment program at UCI, and if students ultimately transfer to UCI upon earning their associate degree.

Despite the low participation rate to date, Baker stresses that community college counselors are not to blame.

“Community college counselors need to know how to advise students with incredibly diverse backgrounds and incredibly diverse goals,” Baker said. “They need to identify who would be a good fit for this program and who is eligible, and then advise them on how to pursue it at each of the different campuses; the process is different at UCI, UCLA, and CSUF. The lack of participation is not a reflection of their efforts.”

Baker’s research focuses on higher educational policy and the effects it has on student persistence and success. In 2019, Baker received a prestigious National Academy of Education Spencer Fellowship to support the third and final part of a study that is examining the complexity of degree requirements in colleges. That is, not the difficulty of the classes in a given major, but how clearly the requirements are presented or explained.

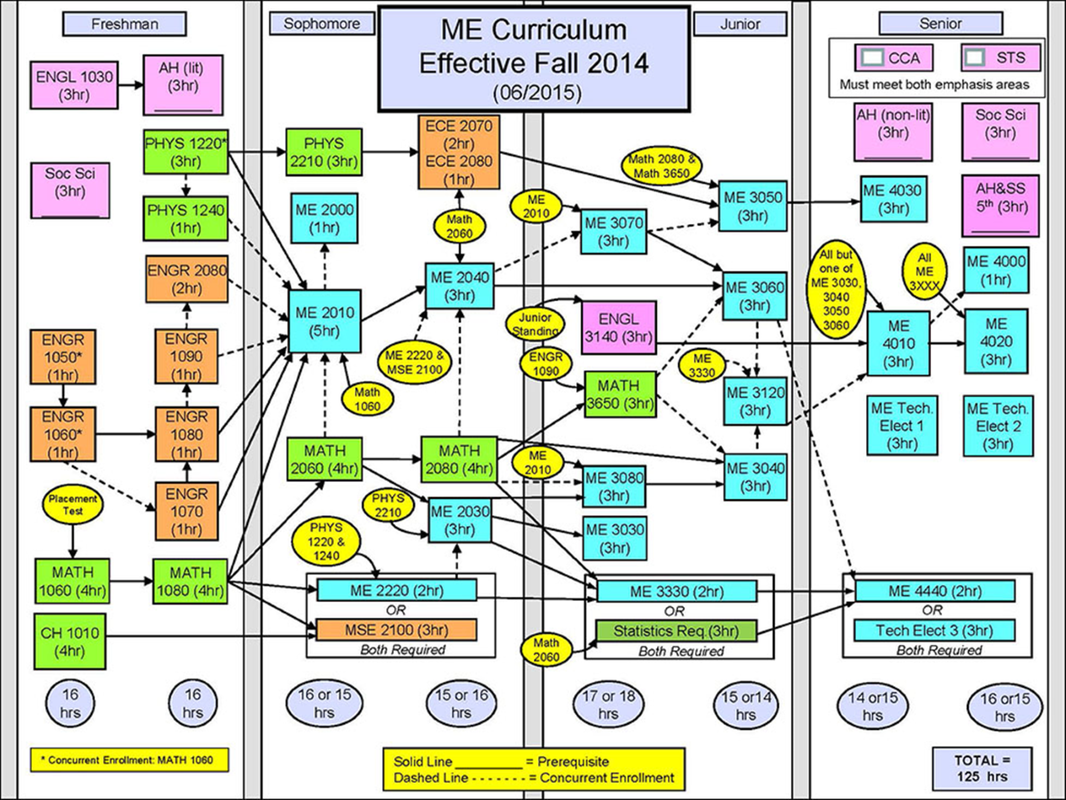

“Figuring out degree requirements can be a confusing process,” Baker said. “There’s a large body of literature that has found that many students mistakenly take classes that didn’t count for their degree requirements, or that they need to enroll in an extra semester because they didn’t know they needed to take a certain class until it was too late.”

Baker began researching the topic in 2016 by looking at the listed degree requirement for four degrees – Economics, Psychology, Biology, and English – at all the UC and CSU campuses. She then assigned values of complexity based on three factors.

With a five-year, $2.5 million grant from the National Science Foundation, Baker is doing just that. This past year, the first of the grant, Baker and Loris Fagioli, director of research at Irvine Valley College, along with a team of undergraduate students, doctoral students, and postdoctoral scholars, conducted 12 focus groups with students and counselors at Orange Coast College, Irvine Valley College, and Saddleback College.

Their preliminary findings revealed that roughly 90 percent of students were unfamiliar with the Cross-Enrollment program. Once learning about it, their interest piqued, but concerns about assimilating, transportation costs, and access to tutoring and library services pervaded.

As did the question of what classes to take, for a few reasons. First, degree requirements are complex and it is difficult to determine which classes can be used to fulfill specific requirements. Second, many students noted that the smaller class sizes and accessible instructors at their community college were what initially attracted them to the school; students were worried that taking a difficult class in an unfamiliar setting might harm their GPA and, ironically, lower their chance of successfully transferring.

Now that Baker has discovered these concerns, she and her project team are establishing an intervention that will provide a range of services to groups of community college students at the partner campuses. For example, one group of students will simply receive information about the program. Another group might receive information and a parking stipend. Yet another might receive information, parking, assistance in filling out the required paperwork, and guidance on selecting which class to enroll in.

Baker and her team will then follow the students for five years to see what helps increase the rate of participation in the Cross-Enrollment program at UCI, and if students ultimately transfer to UCI upon earning their associate degree.

Despite the low participation rate to date, Baker stresses that community college counselors are not to blame.

“Community college counselors need to know how to advise students with incredibly diverse backgrounds and incredibly diverse goals,” Baker said. “They need to identify who would be a good fit for this program and who is eligible, and then advise them on how to pursue it at each of the different campuses; the process is different at UCI, UCLA, and CSUF. The lack of participation is not a reflection of their efforts.”

Baker’s research focuses on higher educational policy and the effects it has on student persistence and success. In 2019, Baker received a prestigious National Academy of Education Spencer Fellowship to support the third and final part of a study that is examining the complexity of degree requirements in colleges. That is, not the difficulty of the classes in a given major, but how clearly the requirements are presented or explained.

“Figuring out degree requirements can be a confusing process,” Baker said. “There’s a large body of literature that has found that many students mistakenly take classes that didn’t count for their degree requirements, or that they need to enroll in an extra semester because they didn’t know they needed to take a certain class until it was too late.”

Baker began researching the topic in 2016 by looking at the listed degree requirement for four degrees – Economics, Psychology, Biology, and English – at all the UC and CSU campuses. She then assigned values of complexity based on three factors.

|

First – how many distinct course categories (groups of classes that are completely interchangeable) there are. Second – how many operators there are in the requirements: “Take Class A and Class B” or “Class B can fulfill Requirement 1 or Requirement 2, but not both,” for example. Finally – how many unique ways there are to graduate.

Baker called this a “fun exercise,” but not one that would prove itself very useful if it did not match what students considered to be complex. Therefore, Baker began surveying students to learn their preferences among the ways major requirements are presented. Through this process, Baker established guidelines for departments that reflected students’ opinions of complexity. As part of the Spencer Fellowship, Baker is now coding the complexity of major requirements for eight different majors on six community college campuses. She will then combine this with data on student course taking from those community colleges. Using major- and campus-fixed effects, she will determine if the complexity of major requirements is correlated with a student’s probability of graduating, and their efficiency in graduating. |

“Our goal is to see if our measures of complexity are actually correlated with student outcomes,” Baker said. “There is important complexity – requiring a set of classes that will stretch a student and force them to think in different ways is good. Taking classes that you did not need to because you thought you had to is not good. We hope this study provides usable information for departments on how they can organize their classes in a way that is much easier for students to understand without sacrificing any rigor or breadth.”

Reducing the complexity of degree requirements might take on added importance this fall and in the near future – Baker anticipates the COVID-19 pandemic to lead to increased enrollment at community colleges.

“At least for a while, more students will be enrolling in community colleges and they will be facing capacity constraints, so hopefully my research leads institutions to think about how to design themselves in ways that are helping student decision making,” Baker said. “I think there are things that schools can address relatively easily, and they can have a positive effect.”

Baker sees the California Community Colleges System as an underappreciated, fascinating system. “They are rich, effective places, and they are under-resourced and being asked to do so much,” Baker said. “I marvel at how much is happening there and I learn so much from the students, faculty, and counselors at the schools. The thought that my work could be of service to them is exciting.”

Baker enjoys working at UCI and the School of Education because of the school’s well-deserved pride at being an effective engine of social mobility. Additionally, Baker appreciates that the mission of the university and the School of Education are aligned with her research.

“Being at a school that is willing to examine itself is great, as is the fact that our faculty and administrators want to learn how to best serve students,” Baker said. “There’s this attitude and mission on campus that we’re going to study ourselves and learn about students and do this better.

“For someone who studies higher education, it’s such an inspiring place to work.”

Reducing the complexity of degree requirements might take on added importance this fall and in the near future – Baker anticipates the COVID-19 pandemic to lead to increased enrollment at community colleges.

“At least for a while, more students will be enrolling in community colleges and they will be facing capacity constraints, so hopefully my research leads institutions to think about how to design themselves in ways that are helping student decision making,” Baker said. “I think there are things that schools can address relatively easily, and they can have a positive effect.”

Baker sees the California Community Colleges System as an underappreciated, fascinating system. “They are rich, effective places, and they are under-resourced and being asked to do so much,” Baker said. “I marvel at how much is happening there and I learn so much from the students, faculty, and counselors at the schools. The thought that my work could be of service to them is exciting.”

Baker enjoys working at UCI and the School of Education because of the school’s well-deserved pride at being an effective engine of social mobility. Additionally, Baker appreciates that the mission of the university and the School of Education are aligned with her research.

“Being at a school that is willing to examine itself is great, as is the fact that our faculty and administrators want to learn how to best serve students,” Baker said. “There’s this attitude and mission on campus that we’re going to study ourselves and learn about students and do this better.

“For someone who studies higher education, it’s such an inspiring place to work.”