WRITE Center Helps Teachers Grapple with ChatGPT and Future of Writing Instruction

Thousands of educators around the world connect virtually for the UCI School of Education-hosted conversation about the new AI-writing tool.

|

By Christine Byrd

February 6, 2023 It’s hard to think of a new technology that has shaken educators to their core as swiftly and profoundly as ChatGPT. Within days of the free public release of ChatGPT3.5, the artificial intelligence writing tool had over 1 million users, and headlines decried the death of high school writing classes and the college essay. School districts in Los Angeles, New York and Seattle banned the website within weeks, and some educators began revamping their courses to preserve academic integrity in the face of this potential new tool for plagiarism. |

“A lot of teachers may be feeling like the apocalypse is here,” said Carol Booth Olson, UCI professor of education emerita and principal investigator of UCI School of Education’s WRITE Center (Writing Research to Improve Teaching and Evaluation), which is funded by a grant from the U.S. Department of Education.

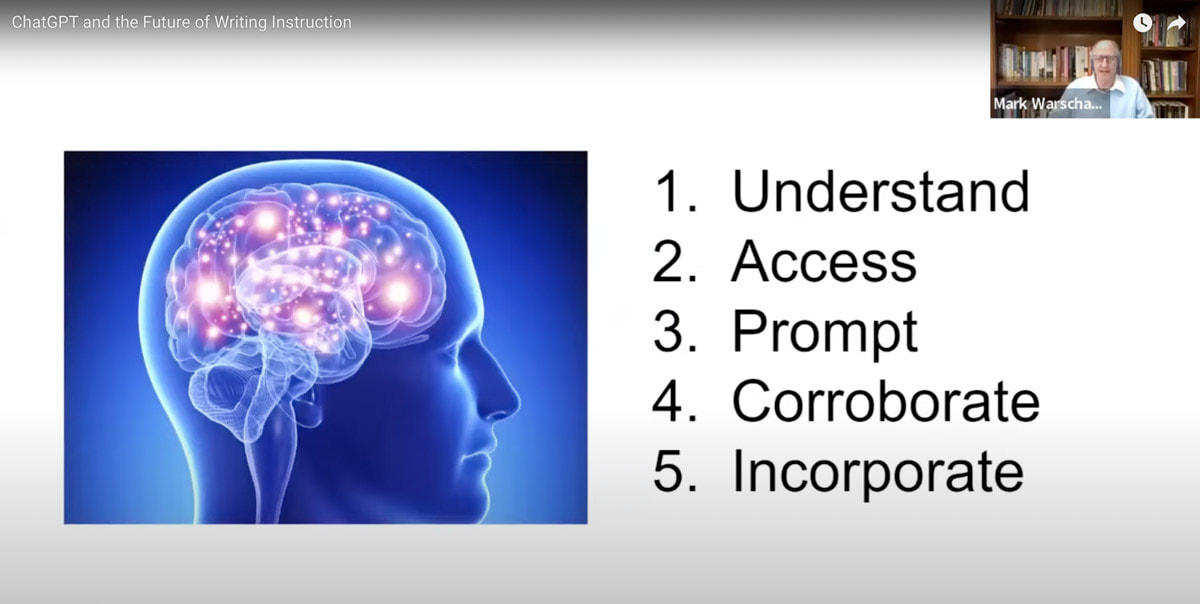

In response to the surging interest in the teaching community, the WRITE Center and the National Writing Project (NWP) gathered leading experts for the webinar “ChatGPT and the Future of Writing Instruction” on January 26 – which drew more than 3,000 registrants from Australia, Canada and across the U.S. to hear ideas and advice on how to grapple with this new element in education.

In response to the surging interest in the teaching community, the WRITE Center and the National Writing Project (NWP) gathered leading experts for the webinar “ChatGPT and the Future of Writing Instruction” on January 26 – which drew more than 3,000 registrants from Australia, Canada and across the U.S. to hear ideas and advice on how to grapple with this new element in education.

Emerging technology

Released by San Francisco-based artificial intelligence company OpenAI in late November 2022, ChatGPT is essentially a souped-up version of the text prediction tool you’ve probably used when writing emails, according to Mark Warschauer, professor of education and co-principal investigator of the WRITE Center. A type of “large language model,” ChatGPT crawled the web for eight years and consumed hundreds of thousands of books, learning to produce natural-sounding, conversational text.

“It has no intelligence, no wisdom,” said Warschauer. Yet ChatGPT can create outlines, write essays, summarize articles, or produce study guides. It can even do aspects of a teacher’s job, such as creating a lesson plan or critiquing a student essay.

While early users quickly pointed out major shortcomings in the tool – from reflecting gender and racial bias to producing flat-out false information – ChatGPT nevertheless represents a quantum leap in writing technology.

As 2023 dawned, many educators already exhausted to the point of burnout three years into the COVID-19 pandemic were in panic over the havoc ChatGPT might wreak on their efforts to teach students to write and think for themselves. But leaders at the WRITE Center and NWP took a more optimistic view.

“This is a really rare and exciting time, teacher to teacher, to get in there, play with it and start to talk to other teachers about the one thing that nobody knows: Nobody knows at this moment how ChatGPT should be used in education,” said Elyse Eidman-Aadahl, executive director of the NWP. “We can inform that conversation right from the start, and that’s why I’m such a proponent of having teachers get in there.”

The education experts and practitioners featured in the webinar included Olson, Warschauer, Eidman-Aadahl, UCI project scientist Tamara Tate, and two high school teachers, Chris Sloan and Paul Allison.

Here are some of their key pieces of advice for teachers.

Released by San Francisco-based artificial intelligence company OpenAI in late November 2022, ChatGPT is essentially a souped-up version of the text prediction tool you’ve probably used when writing emails, according to Mark Warschauer, professor of education and co-principal investigator of the WRITE Center. A type of “large language model,” ChatGPT crawled the web for eight years and consumed hundreds of thousands of books, learning to produce natural-sounding, conversational text.

“It has no intelligence, no wisdom,” said Warschauer. Yet ChatGPT can create outlines, write essays, summarize articles, or produce study guides. It can even do aspects of a teacher’s job, such as creating a lesson plan or critiquing a student essay.

While early users quickly pointed out major shortcomings in the tool – from reflecting gender and racial bias to producing flat-out false information – ChatGPT nevertheless represents a quantum leap in writing technology.

As 2023 dawned, many educators already exhausted to the point of burnout three years into the COVID-19 pandemic were in panic over the havoc ChatGPT might wreak on their efforts to teach students to write and think for themselves. But leaders at the WRITE Center and NWP took a more optimistic view.

“This is a really rare and exciting time, teacher to teacher, to get in there, play with it and start to talk to other teachers about the one thing that nobody knows: Nobody knows at this moment how ChatGPT should be used in education,” said Elyse Eidman-Aadahl, executive director of the NWP. “We can inform that conversation right from the start, and that’s why I’m such a proponent of having teachers get in there.”

The education experts and practitioners featured in the webinar included Olson, Warschauer, Eidman-Aadahl, UCI project scientist Tamara Tate, and two high school teachers, Chris Sloan and Paul Allison.

Here are some of their key pieces of advice for teachers.

Address academic integrity. Banning ChatGPT from schools won’t keep students from accessing it from their home computers or smartphones, Warschauer pointed out.

“We need to get buy-in, keep our eyes out, talk to students about the ethics behind it, and eventually try to integrate it into the classroom in an ethical way,” said Warschauer.

Programmers are already working on ways to add a digital watermark to text created by ChatGPT, or another tool to identify AI-generated writing. But the speakers urged teachers to begin talking to students about proper use of the tool and class expectations.

Adjust assignments. Some teachers who are concerned that students might use ChatGPT to produce their school work are modifying their assignments to make them harder for a computer to complete. Those changes may, ultimately, make for better assignments overall.

“Writing to an output – like a five-paragraph essay, like a state assessment test – a lot of those are occasions where young people are themselves thinking a little bit like a bot when they put together their text,” said Eidman-Aadahl.

Experts urge teachers to consider what students can do that ChatGPT cannot, such as make personal connections and judgements, and to place emphasis on writing that requires meaningful engagement with the material. Then, students can use ChatGPT more as a tool to help them through specific parts of the writing process.

Use it as a teaching tool. Professional writers and researchers who dove into experimenting with ChatGPT have already begun sharing how they are leveraging the tool to assist in their process. Educators, too, can look for ways to harness the technology as a teaching tool.

“On a 6-point scale for the school-based essay writing taught in English language arts classes, ChatGPT can produce something that’s about a 4. So if I were a teacher, I would use it to produce a base draft and with the class together, revise it to be even better, looking at word choice and evidence it used,” Olson said.

High school teachers Chris Sloan and Paul Allison shared case studies during the webinar of how they have their students leveraging ChatGPT in research and writing projects. For example, they’ve asked students to use it to evaluate the credibility of articles they find online, produce summaries of articles, help format citations, and even provide cursory feedback on a draft.

Not all teachers welcome these ideas – including many in the webinar chat.

“Despite the enthusiasm some will no doubt feel for ChatGPT, a large number of teachers feel a potential loss of engagement, purpose, and identity as they learn about the power of ChatGPT,” said Jim Burke, an educator and author of several books on teaching writing who attended the webinar and shared his thoughts afterward.

“Along with these problems, teachers worry that such applications as ChatGPT will fundamentally change the nature of their relationship with their discipline and students, forcing them (as many already feel the need to do now) to worry more about catching than teaching kids,” Burke added. “This shift threatens to make teachers feel like technicians instead of teachers.”

Try it yourself. Students aren’t the only ones who can leverage ChatGPT to make their lives easier. Sloan shared how he used ChatGPT as a “thinking partner,” asking a series of questions to develop a carefully crafted essay prompt for his students.

In addition, Olson said that because ChatGPT can give feedback that’s “not wonderful, but adequate in most cases,” teachers facing a stack of 250 essays to review may choose to have students run their essays through ChatGPT, make revisions, and then write the teacher a letter reflecting on what they chose to revise, and why.

Consider the circumstances. Warschauer points out that for some, the new technology could be a powerful tool for good. For example, ChatGPT offers better translation capabilities than Google Translate, and could be instrumental in helping scientists or business people who need to publish research and reports in their non-native language. And for students or workers with dyslexia or a learning disability, the tool could help them easily produce emails, reports or narratives based on information they provide.

But here again, ChatGPT blurs the traditionally accepted lines around academic integrity and plagiarism.

Beware of equity issues. Equity issues permeate conversations about educational uses of ChatGPT. Though it’s available for free now, experts point out that the technology that powers ChatGPT will eventually go behind a paywall, and likely be packaged with other tools and sold to businesses and schools, perhaps through purchases like Microsoft Office.

“That will further widen the digital divide, which is worrisome, as not all students will have equal access to the technology” said Olson.

Yet, if AI-generated writing is going to become a standard part of the business world, then students will need to learn how to use the tools ethically and effectively in school.

“We have to think about this as a whole ecosystem that needs to be imbued with our very best expectations of what it would mean to prepare our young people to thrive in a future that includes AI,” said Eidman-Aadahl.

“We need to get buy-in, keep our eyes out, talk to students about the ethics behind it, and eventually try to integrate it into the classroom in an ethical way,” said Warschauer.

Programmers are already working on ways to add a digital watermark to text created by ChatGPT, or another tool to identify AI-generated writing. But the speakers urged teachers to begin talking to students about proper use of the tool and class expectations.

Adjust assignments. Some teachers who are concerned that students might use ChatGPT to produce their school work are modifying their assignments to make them harder for a computer to complete. Those changes may, ultimately, make for better assignments overall.

“Writing to an output – like a five-paragraph essay, like a state assessment test – a lot of those are occasions where young people are themselves thinking a little bit like a bot when they put together their text,” said Eidman-Aadahl.

Experts urge teachers to consider what students can do that ChatGPT cannot, such as make personal connections and judgements, and to place emphasis on writing that requires meaningful engagement with the material. Then, students can use ChatGPT more as a tool to help them through specific parts of the writing process.

Use it as a teaching tool. Professional writers and researchers who dove into experimenting with ChatGPT have already begun sharing how they are leveraging the tool to assist in their process. Educators, too, can look for ways to harness the technology as a teaching tool.

“On a 6-point scale for the school-based essay writing taught in English language arts classes, ChatGPT can produce something that’s about a 4. So if I were a teacher, I would use it to produce a base draft and with the class together, revise it to be even better, looking at word choice and evidence it used,” Olson said.

High school teachers Chris Sloan and Paul Allison shared case studies during the webinar of how they have their students leveraging ChatGPT in research and writing projects. For example, they’ve asked students to use it to evaluate the credibility of articles they find online, produce summaries of articles, help format citations, and even provide cursory feedback on a draft.

Not all teachers welcome these ideas – including many in the webinar chat.

“Despite the enthusiasm some will no doubt feel for ChatGPT, a large number of teachers feel a potential loss of engagement, purpose, and identity as they learn about the power of ChatGPT,” said Jim Burke, an educator and author of several books on teaching writing who attended the webinar and shared his thoughts afterward.

“Along with these problems, teachers worry that such applications as ChatGPT will fundamentally change the nature of their relationship with their discipline and students, forcing them (as many already feel the need to do now) to worry more about catching than teaching kids,” Burke added. “This shift threatens to make teachers feel like technicians instead of teachers.”

Try it yourself. Students aren’t the only ones who can leverage ChatGPT to make their lives easier. Sloan shared how he used ChatGPT as a “thinking partner,” asking a series of questions to develop a carefully crafted essay prompt for his students.

In addition, Olson said that because ChatGPT can give feedback that’s “not wonderful, but adequate in most cases,” teachers facing a stack of 250 essays to review may choose to have students run their essays through ChatGPT, make revisions, and then write the teacher a letter reflecting on what they chose to revise, and why.

Consider the circumstances. Warschauer points out that for some, the new technology could be a powerful tool for good. For example, ChatGPT offers better translation capabilities than Google Translate, and could be instrumental in helping scientists or business people who need to publish research and reports in their non-native language. And for students or workers with dyslexia or a learning disability, the tool could help them easily produce emails, reports or narratives based on information they provide.

But here again, ChatGPT blurs the traditionally accepted lines around academic integrity and plagiarism.

Beware of equity issues. Equity issues permeate conversations about educational uses of ChatGPT. Though it’s available for free now, experts point out that the technology that powers ChatGPT will eventually go behind a paywall, and likely be packaged with other tools and sold to businesses and schools, perhaps through purchases like Microsoft Office.

“That will further widen the digital divide, which is worrisome, as not all students will have equal access to the technology” said Olson.

Yet, if AI-generated writing is going to become a standard part of the business world, then students will need to learn how to use the tools ethically and effectively in school.

“We have to think about this as a whole ecosystem that needs to be imbued with our very best expectations of what it would mean to prepare our young people to thrive in a future that includes AI,” said Eidman-Aadahl.

What’s next

For now, the millions of people using the current version of ChatGPT are essentially training the next generation of the technology, which will be even more powerful than the current version.

Experts anticipate that as the novelty wears off – and as the paywall goes up – teachers and students will settle into a new standard of practice with the technology. Warschauer compared it to the graphing calculator, which posed challenges to math teachers when it was first introduced but has become an indispensable tool in higher-level math courses.

Warschauer quoted English teachers’ beloved Shakespeare: “There is nothing either good or bad but thinking makes it so.”

“ChatGPT is not automatically all good, it’s not automatically all bad,” he said. “The way we think about it affects how we use it in instruction.”

And ChatGPT may help with the writing, but the thinking is still up to students and teachers.

For now, the millions of people using the current version of ChatGPT are essentially training the next generation of the technology, which will be even more powerful than the current version.

Experts anticipate that as the novelty wears off – and as the paywall goes up – teachers and students will settle into a new standard of practice with the technology. Warschauer compared it to the graphing calculator, which posed challenges to math teachers when it was first introduced but has become an indispensable tool in higher-level math courses.

Warschauer quoted English teachers’ beloved Shakespeare: “There is nothing either good or bad but thinking makes it so.”

“ChatGPT is not automatically all good, it’s not automatically all bad,” he said. “The way we think about it affects how we use it in instruction.”

And ChatGPT may help with the writing, but the thinking is still up to students and teachers.