The Equation for Science Learning

Through an NSF CAREER grant, Associate Professor Hosun Kang is supporting students from historically marginalized communities in learning about science in a meaningful way.

|

Despite decades of reform efforts and the use of experiential activities in science instruction, research indicates that science classroom learning for students remains largely procedural, undemanding, and disconnected from the development of substantive scientific ideas.

A lifelong advocate of civic responsibility, equality, and science learning, Associate Professor Hosun Kang is working with the Tustin Unified School District, its teachers, teacher leaders, and students to change science instruction from rote memorization to an engaging and empowering learning experience that supports historically marginalized student populations. “This project focuses on supporting Latinx and multilingual students in learning about science in a meaningful way,” Kang said. “The discourse over who can and cannot succeed in the science classroom has been racialized. Even Latinx students who routinely receive A’s in their classwork don’t self-identify as someone capable of succeeding.” Kang is hoping to empower both students and teachers through the partnership. Working together, she explains, the team can transform science teaching and learning at the classroom level by developing new curricula and assessments for learning, as well as generate systematic research that contributes to understanding how science teachers and students learn. |

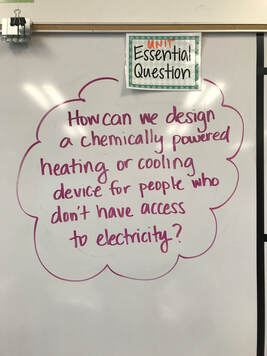

This past year, the first of the five-year project, Kang and her research team worked with chemistry and physics teachers to re-frame curriculum to both relate to students and imbue them with a sense of civic purpose. Instead of simply plugging numbers to do stoichiometry, for example, students are asked, “How can we design a chemically powered heating or cooling device for people who don’t have access to electricity?”

Early results are encouraging. Kang mentions a Latinx high school female student who historically received C’s in her science classes. When a newly designed chemistry project posed the question, “How can we use chemistry to make a difference in our community?” The student responded by designing and creating a “heating blanket” for homeless individuals and developing a website to share the product and her story. She received an A+ for the project.

“Everyone deserves a high-quality science learning experience,” Kang said. “Not everyone is going to become a scientist, but we encounter science-related problems every day – climate change, wildfires, COVID-19 and immunization. Science impacts us individually and as a society, and it’s important that people use science and enjoy learning about it.”

Early results are encouraging. Kang mentions a Latinx high school female student who historically received C’s in her science classes. When a newly designed chemistry project posed the question, “How can we use chemistry to make a difference in our community?” The student responded by designing and creating a “heating blanket” for homeless individuals and developing a website to share the product and her story. She received an A+ for the project.

“Everyone deserves a high-quality science learning experience,” Kang said. “Not everyone is going to become a scientist, but we encounter science-related problems every day – climate change, wildfires, COVID-19 and immunization. Science impacts us individually and as a society, and it’s important that people use science and enjoy learning about it.”

|

Participating teachers also laud the program’s structure and its ability to produce tangible, practical solutions to implement immediately.

“Working with colleagues has helped me become a better teacher because I get to plan with them and see how they teach the lesson,” said Paul Tschida, a physics teacher at Tustin High School. “Even though we teach something in different ways, I still take ideas from their classrooms to bring back to my class right away to see what works best for students.” “You’re not just given a tool to use, like many professional development programs provide, but instead you are given an opportunity to improve your own work and focus your energy to improve what you are already doing,” said Lindsay Fay, chemistry teacher at Tustin High School. “It is really tailored to exactly what you want – I’m not wasting time on something theoretical or another class that isn’t what I teach.” |

The work with Tustin Unified School District is part of Kang’s research for an NSF CAREER grant, Expanding Latinxs’ Opportunities to Develop Complex Thinking in Secondary Science Classrooms through a Research-Practice Partnership. CAREER grants are given “in support of early-career faculty who have the potential to serve as academic role models in research and education and to lead advances in the mission of their department or organization.”

Kang is also faculty advisor for the UCI Science Project, a new initiative within the UCI Teacher Academy. The UCI Science Project is committed to providing professional development opportunities for local K-12 science teachers focused on Next Generation Science Standards, and, Kang explains, to make the world a better place through the teaching and learning of science.

“We have to address the new standards, but we cannot do that without thinking about the injustice and inequity that our students experience,” Kang said. “We are creating a space for teachers to engage in this conversation.”

Kang is also faculty advisor for the UCI Science Project, a new initiative within the UCI Teacher Academy. The UCI Science Project is committed to providing professional development opportunities for local K-12 science teachers focused on Next Generation Science Standards, and, Kang explains, to make the world a better place through the teaching and learning of science.

“We have to address the new standards, but we cannot do that without thinking about the injustice and inequity that our students experience,” Kang said. “We are creating a space for teachers to engage in this conversation.”

|

Kang earned her Ph.D. in Curriculum, Instruction and Teacher Education from Michigan State University. While a doctoral student, Kang drove three hours round-trip, weekly, to an urban middle school for an entire year to follow a group of seventh- and eighth-grade girls. She began shadowing the students before the day began until its completion, through every class, including lunch and physical education.

She found that the Black students’ discourse and attitude toward science dramatically changed over the course of just one year. Their brilliant ideas and rich experiences outside the classrooms were not leveraged, their peers did not recognize them as capable of doing the work, and support was not provided. In essence, Kang saw how a Black girl cumulatively changed her relationships with science, school, and peers through social interactions before her very eyes. “That still resonates with me today,” Kang said. “Before that, I was looking at science teaching and learning from the teacher’s perspective, but after that I learned how difficult it is for some students, in particular students of color, to navigate spaces, and I began looking at problems from both a teacher and student perspective.” |

Kang used data from this project in a 2019 Science Education publication – How do middle school girls of color develop STEM identities? The paper was one of the most downloaded in the Science Education Journal in 2019.

Originally from South Korea, Kang taught science to middle and high school students in the country for 7 ½ years. Over that time, she desired to learn more about education so that she could better support the students that were struggling at school.

Kang cites a former mentor, Geun-Choon Lee, whom she met when she began her career as a novice teacher, as an ongoing inspiration for her work.

“She showed me what it means to be a true educator, and how an educator can care for the students, listen and be respectful, and have integrity as an educator. She became a model in my mind of how I want to conduct myself professionally.”

As an immigrant scholar herself, Kang said she empathizes and connects with non-white multilingual students in the classroom. Dating back to her time as a graduate student, this connection has informed her research.

“I want to continue working on the ground floor with students every day,” Kang said. “The work is inspiring to me, and I feel like I can give back to the community through my research – I view it as my civic responsibility.”

Originally from South Korea, Kang taught science to middle and high school students in the country for 7 ½ years. Over that time, she desired to learn more about education so that she could better support the students that were struggling at school.

Kang cites a former mentor, Geun-Choon Lee, whom she met when she began her career as a novice teacher, as an ongoing inspiration for her work.

“She showed me what it means to be a true educator, and how an educator can care for the students, listen and be respectful, and have integrity as an educator. She became a model in my mind of how I want to conduct myself professionally.”

As an immigrant scholar herself, Kang said she empathizes and connects with non-white multilingual students in the classroom. Dating back to her time as a graduate student, this connection has informed her research.

“I want to continue working on the ground floor with students every day,” Kang said. “The work is inspiring to me, and I feel like I can give back to the community through my research – I view it as my civic responsibility.”