Positive Reinforcement

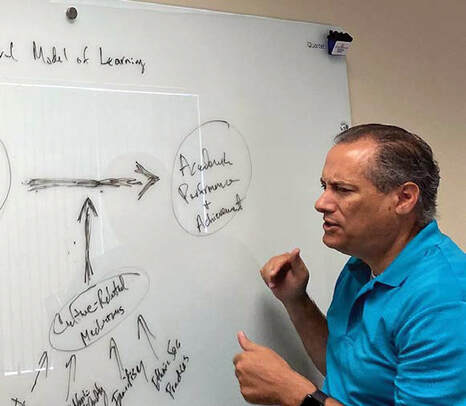

Working with a wide range of ethnicities and races and in various regions across the nation, Professor Gustavo Carlo is dedicated to understanding the positive social development in culturally diverse children and adolescents.

|

Sitting in his Irvine office, Professor Gustavo Carlo pores over data from one of his latest research grants – studying the health and safety risks of cattle feedlot workers in Kansas and Nebraska, and the consequences of their stress and injuries on their children’s development.

It might not make much sense why a professor at a school of education in Southern California is studying farm workers in the Midwest. It would, however, if you knew Carlo, who jokes, “My research is all over the place.” The common thread across his varied research is an emphasis on positive social development and health in culturally diverse children and adolescents. “A lot of research, especially research that focuses on ethnic and racial minority populations, tends to emphasize deficit and risk factors, and I believe that overemphasis can contribute to negative stereotypes and stigma,” Carlo said. “I tend to focus on what are the predictors and correlates of positive outcomes.” |

As of summer 2021, he has published more than 200 books, chapters and research papers. To date, his research has studied Latino/a, African American and Asian American kids in Arizona, Nebraska, Missouri, Florida, California, Michigan, Pennsylvania, Kansas, and Texas. And that’s just the United States; his studies also include populations in Turkey, Argentina, Nicaragua, Korea, Germany and more.

“We don’t really set any limits in terms of the diversity and the range of cultural backgrounds we’re interested in because, ultimately, it’s important to learn from all different backgrounds so that the work can inform the core theories and models that we’re trying to develop to explain positive social development,” Carlo said.

One of the first milestones for Carlo came from a National Science Foundation-funded grant that studied the socialization of positive social behavior in Mexican American adolescents. It was not only the first study ever that focused on positive youth development in a Latino/a sample, but was also the first study in which researchers examined culture- related mechanisms and identified which mechanisms could predict prosocial behaviors – behaviors such as helping, sharing, cooperating and volunteering.

Several research papers were borne out of the grant. Chief among the findings: kids who more strongly endorsed a sense of ethnic identity reported higher levels of prosocial behaviors; cultural-related mechanisms had their own unique, predictive effects; there exists prosocial behaviors unique to Mexican heritage kids; and parents who engaged in practices that taught children about their ethnicity reported higher instances of prosocial behaviors in their kids.

“That broke a lot of new ground for us and in the field,” Carlo said.

Since then, Carlo has led research into myriad topics, and produced many “firsts.”

In a 2018 article published in Child Development, Carlo studied a unique way of parenting that Mexican-heritage fathers exhibited. The style, called “no-nonsense” parenting, is akin to what’s called “authoritarian” parenting in White, European American families.

Authoritarian parenting has previously shown to be detrimental to a White, European American child’s health and development. The “no-nonsense” parenting style in Mexican-heritage fathers, on the other hand, did not show any positive or negative effects on their teens’ prosocial behaviors.

“We don’t really set any limits in terms of the diversity and the range of cultural backgrounds we’re interested in because, ultimately, it’s important to learn from all different backgrounds so that the work can inform the core theories and models that we’re trying to develop to explain positive social development,” Carlo said.

One of the first milestones for Carlo came from a National Science Foundation-funded grant that studied the socialization of positive social behavior in Mexican American adolescents. It was not only the first study ever that focused on positive youth development in a Latino/a sample, but was also the first study in which researchers examined culture- related mechanisms and identified which mechanisms could predict prosocial behaviors – behaviors such as helping, sharing, cooperating and volunteering.

Several research papers were borne out of the grant. Chief among the findings: kids who more strongly endorsed a sense of ethnic identity reported higher levels of prosocial behaviors; cultural-related mechanisms had their own unique, predictive effects; there exists prosocial behaviors unique to Mexican heritage kids; and parents who engaged in practices that taught children about their ethnicity reported higher instances of prosocial behaviors in their kids.

“That broke a lot of new ground for us and in the field,” Carlo said.

Since then, Carlo has led research into myriad topics, and produced many “firsts.”

In a 2018 article published in Child Development, Carlo studied a unique way of parenting that Mexican-heritage fathers exhibited. The style, called “no-nonsense” parenting, is akin to what’s called “authoritarian” parenting in White, European American families.

Authoritarian parenting has previously shown to be detrimental to a White, European American child’s health and development. The “no-nonsense” parenting style in Mexican-heritage fathers, on the other hand, did not show any positive or negative effects on their teens’ prosocial behaviors.

|

“A lot of research, especially research that focuses on ethnic and racial minority populations, tends to emphasize deficit and risk factors, and I believe that overemphasis can contribute to negative stereotypes and stigma. I tend to focus on what are the predictors and correlates of positive outcomes.” - Gustavo Carlo |

“This is consistent with work that has been done in Asian American and African American families – where it’s referred to as ‘tiger parenting’ and ‘no- nonsense’ parenting, respectively – and where there is also no detrimental effect under this parenting style,” Carlo explained. “This is the first study to demonstrate that it also has no effect on Latino/a kids’ prosocial behaviors.”

The same study also, for the first time, demonstrated that kids who exhibit high levels of prosocial behaviors early in life achieved better academic outcomes later in life – in this case the prosocial behaviors in seventh grade and the academic outcomes in 10th grade. |

“This has major implications and opens the door to potential interventions where you can address the academic disparities that exist,” Carlo said.

Carlo is currently working on a grant from the John Templeton Foundation, which will be the first study to demonstrate the “altruism born of suffering” concept in an ethnic minority sample.

The study analyzes kids who reported traumatic experiences in fifth grade and their eventual propensity to engage in altruistic or morally exemplar behaviors. Preliminary evidence shows that there is a small group of Mexican-heritage kids who demonstrate high levels of altruistic behavior in young adulthood, and that there exists a growth trigger mechanism that leads to an increase in such behaviors. Furthermore, the growth trigger mechanism differs between boys and girls.

Carlo is currently working on a grant from the John Templeton Foundation, which will be the first study to demonstrate the “altruism born of suffering” concept in an ethnic minority sample.

The study analyzes kids who reported traumatic experiences in fifth grade and their eventual propensity to engage in altruistic or morally exemplar behaviors. Preliminary evidence shows that there is a small group of Mexican-heritage kids who demonstrate high levels of altruistic behavior in young adulthood, and that there exists a growth trigger mechanism that leads to an increase in such behaviors. Furthermore, the growth trigger mechanism differs between boys and girls.

|

“For girls, those who reported higher levels of familismo showed increases in altruistic behaviors,” Carlo explained. “For boys, it was those who utilized active coping mechanisms that reported an increase in altruistic behaviors. It’s very exciting to show supportive evidence for this idea of ‘altruism born of suffering,’ but even better to show that there can be mechanisms that trigger it, and that they differ for Latino boys versus Latino girls.”

Born in San Juan, Puerto Rico, Carlo spent his high school and college years in Miami. His interest in academia and research piqued during an undergraduate Psychology class at Florida International University, when he volunteered to conduct research alongside Professor Bill Kurtines. “He took me under his wing and transformed my life. I found possibilities that I had never known about before, and before I knew it, I was drawn into this field of moral development.” Carlo attended Arizona State University and earned a Ph.D. in Developmental Psychology. There he worked with Nancy Eisenberg and George Knight, both of whom he cites as mentors. |

“They opened my eyes to this void in the field of positive development in Latino kids and in ethnic- and racial-minority kids,” Carlo said. “That became my niche.”

Prior to joining the UCI School of Education in summer 2020, Carlo was the Millsap Endowed Professor of Diversity and Multicultural Studies at the University of Missouri and co-director and founder of the university’s Center for Children and Families Across Cultures.

It was not easy to leave an endowed professorship, Carlo said, but ultimately the impressive faculty – both senior and junior – and diversity of the UCI School of Education convinced him to move.

As did the school’s multidisciplinary nature. This facet, Carlo explains, gives him the freedom to conduct his research.

“My work isn’t what you would expect a school of education professor to be doing, but it’s the real world, and the real world is complex – it isn’t a matter of one factor predicting outcomes and explaining everything that happens,” Carlo said. “That complexity necessitates that we think outside of the box, and that’s what we all do at the UCI School of Education.”

Prior to joining the UCI School of Education in summer 2020, Carlo was the Millsap Endowed Professor of Diversity and Multicultural Studies at the University of Missouri and co-director and founder of the university’s Center for Children and Families Across Cultures.

It was not easy to leave an endowed professorship, Carlo said, but ultimately the impressive faculty – both senior and junior – and diversity of the UCI School of Education convinced him to move.

As did the school’s multidisciplinary nature. This facet, Carlo explains, gives him the freedom to conduct his research.

“My work isn’t what you would expect a school of education professor to be doing, but it’s the real world, and the real world is complex – it isn’t a matter of one factor predicting outcomes and explaining everything that happens,” Carlo said. “That complexity necessitates that we think outside of the box, and that’s what we all do at the UCI School of Education.”