Teaching for Justice

Amid the dramatic rise in anti-Asian hate, educators share resources and build community

|

By Christine Byrd Growing up in the San Gabriel Valley’s thriving Chinese American community, Stacy Yung knew her great-grandfathers were buried in the nearby Chinese Cemetery of Los Angeles without their wives or daughters, but no one ever discussed the history that shaped her family’s experience. Not until Yung took an Asian American studies course as a UCI undergraduate did she begin to understand the immigration laws that for decades limited Chinese immigration and prevented Chinese women and families from coming to the U.S., and the many challenges her family faced when they settled in Southern California. |

“It was life changing, seeing my lived experience and my life centered in the class,” she remembers. After finishing her bachelor’s degree in social science that specialized in secondary education in 2007, and her master’s in teaching in 2009, Yung became a middle school history teacher, determined to incorporate experiences and voices that reflected the diversity of her classroom.

“I was going to teach history the way I wished I had learned it, a history that is inclusive of all students’ cultural knowledge, histories and lived experiences,” Yung says.

Now, that vision has turned into a movement: Yung left the classroom to pursue her passion of providing culturally relevant resources and support to teachers, and is part of a team of UCI faculty, staff and alumni intent on empowering educators who want to incorporate Asian American histories and experiences for their K-12 classrooms.

“I was going to teach history the way I wished I had learned it, a history that is inclusive of all students’ cultural knowledge, histories and lived experiences,” Yung says.

Now, that vision has turned into a movement: Yung left the classroom to pursue her passion of providing culturally relevant resources and support to teachers, and is part of a team of UCI faculty, staff and alumni intent on empowering educators who want to incorporate Asian American histories and experiences for their K-12 classrooms.

Combating hate

After COVID-19 was first identified in Wuhan, China, and began circling the globe, hate crimes against Asian Americans skyrocketed, stoked by public figures who dubbed it the “China virus,” and fueled by centuries of structural racism.

In 2020, the OC Human Relations Commission reported an 1,800% increase in anti-Asian hate incidents. California – home to more than 5.8 million Asian Americans – saw hate crimes against Asian Americans continue to rise, increasing 177.5% from 2020 to 2021, according to the California Department of Justice.

Some teachers saw the violence as a predictable result of the lack of education and empathy about the Asian American experience.

“When you don’t know anything about someone’s story, it leaves room for stereotypes and bias,” says Jeff Kim, a teacher in Anaheim Union High School District, adding that he never had a teacher who looked like him going to school in California, and was never taught Asian American studies during K-12.

Through a series of town halls and community forums in 2020 and 2021, Yung and fellow teacher and UCI alumna Virginia Nguyen connected with UCI faculty and staff coalesced around a shared vision: supporting K-12 teachers who want to integrate Asian American studies into their curriculum.

On April 29-30, 2022, the committee presented Teaching for Justice: A Spotlight On Teaching Asian American Studies Across the Curriculum, which drew 250 educators from as far away as Hawaii and New York.

“We are centering teachers’ voices because we know that the classroom is the place where we can support learning for justice,” says Nicole Gilbertson, director of the UCI Teacher Academy and the UCI History Project, kicking off the conference’s first day, which was held virtually. “We honor the knowledge that our committee brings to this work, and also seek to learn from one another.”

Conference organizers assembled a powerhouse lineup of speakers representing a variety of Asian American backgrounds and experiences including educators, researchers, artists, filmmakers, archivists, business owners, community organizers, and even a keynote by television personality and author Lisa Ling.

“When there’s no reference to a community's inclusion throughout history, throughout pop culture, it becomes so easy to overlook an entire community and to even dehumanize it,” says Ling. “And that’s what we’re seeing today.

“It’s our kids who need to be empowered,” Ling continued, reflecting on her two children, ages 9 and 6. “If my generation had the opportunity to immerse ourselves or even to know about this rich Asian American history, I don’t think we would be where we are today with violence and vitriol and racism and discrimination just so pervasive in our culture.”

After COVID-19 was first identified in Wuhan, China, and began circling the globe, hate crimes against Asian Americans skyrocketed, stoked by public figures who dubbed it the “China virus,” and fueled by centuries of structural racism.

In 2020, the OC Human Relations Commission reported an 1,800% increase in anti-Asian hate incidents. California – home to more than 5.8 million Asian Americans – saw hate crimes against Asian Americans continue to rise, increasing 177.5% from 2020 to 2021, according to the California Department of Justice.

Some teachers saw the violence as a predictable result of the lack of education and empathy about the Asian American experience.

“When you don’t know anything about someone’s story, it leaves room for stereotypes and bias,” says Jeff Kim, a teacher in Anaheim Union High School District, adding that he never had a teacher who looked like him going to school in California, and was never taught Asian American studies during K-12.

Through a series of town halls and community forums in 2020 and 2021, Yung and fellow teacher and UCI alumna Virginia Nguyen connected with UCI faculty and staff coalesced around a shared vision: supporting K-12 teachers who want to integrate Asian American studies into their curriculum.

On April 29-30, 2022, the committee presented Teaching for Justice: A Spotlight On Teaching Asian American Studies Across the Curriculum, which drew 250 educators from as far away as Hawaii and New York.

“We are centering teachers’ voices because we know that the classroom is the place where we can support learning for justice,” says Nicole Gilbertson, director of the UCI Teacher Academy and the UCI History Project, kicking off the conference’s first day, which was held virtually. “We honor the knowledge that our committee brings to this work, and also seek to learn from one another.”

Conference organizers assembled a powerhouse lineup of speakers representing a variety of Asian American backgrounds and experiences including educators, researchers, artists, filmmakers, archivists, business owners, community organizers, and even a keynote by television personality and author Lisa Ling.

“When there’s no reference to a community's inclusion throughout history, throughout pop culture, it becomes so easy to overlook an entire community and to even dehumanize it,” says Ling. “And that’s what we’re seeing today.

“It’s our kids who need to be empowered,” Ling continued, reflecting on her two children, ages 9 and 6. “If my generation had the opportunity to immerse ourselves or even to know about this rich Asian American history, I don’t think we would be where we are today with violence and vitriol and racism and discrimination just so pervasive in our culture.”

Thriving together

Educators at the Teaching for Justice conference were eager to incorporate diverse voices into the curriculum – regardless of their own ethnic background, or even the subject they teach.

“As a math teacher, you don’t typically see anyone in my field incorporating any of these things in their lessons,” says Naehee Kwun, Teacher Network Facilitator for UCI’s CalTeach Science & Math program. “It takes more effort and it takes collaboration. I realized that student identities have to connect to what they’re learning and it's our responsibility as teachers to do this.”

One first-year teacher who attended the conference wrote, “At my current site, 55% of the student population is Asian, yet the staff is majority White. With the lack of representation in the staff and the high percentage of Asian American students, I find it vital for students to see themselves in the curriculum they are learning. Though I am a science teacher, I want to challenge my current curriculum and showcase more voices from minority groups.”

For conference organizers, this is exactly the outcome they hoped for.

“I have so much respect for teachers,” says Thuy Vo Dang, curator of the Southeast Asian Archive. “These are the folks who understand how powerful knowledge is, and have that sense of learning from others’ histories and experiences can only enrich your own life and worldview. They harness that and are hopefully going to bring that into the classroom to their students – not to try to flatten out differences, but to coexist and thrive together.”

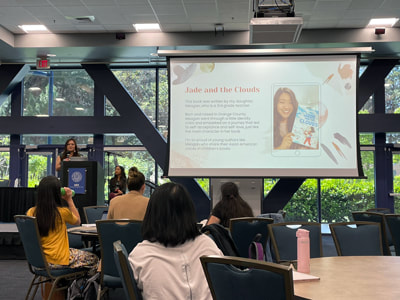

While the first day of the conference was online, day two brought educators from across Orange County to gather in-person at the UCI Student Center and enjoy a sense of catharsis – both from being face-to-face and from finding a sense of community support after such a difficult two years.

“What really stuck with me was how healing the conference was, to me, and to many people,” says Fuko Kiyama, a School of Education Ph.D. student who coordinated the conference volunteers.

Educators at the Teaching for Justice conference were eager to incorporate diverse voices into the curriculum – regardless of their own ethnic background, or even the subject they teach.

“As a math teacher, you don’t typically see anyone in my field incorporating any of these things in their lessons,” says Naehee Kwun, Teacher Network Facilitator for UCI’s CalTeach Science & Math program. “It takes more effort and it takes collaboration. I realized that student identities have to connect to what they’re learning and it's our responsibility as teachers to do this.”

One first-year teacher who attended the conference wrote, “At my current site, 55% of the student population is Asian, yet the staff is majority White. With the lack of representation in the staff and the high percentage of Asian American students, I find it vital for students to see themselves in the curriculum they are learning. Though I am a science teacher, I want to challenge my current curriculum and showcase more voices from minority groups.”

For conference organizers, this is exactly the outcome they hoped for.

“I have so much respect for teachers,” says Thuy Vo Dang, curator of the Southeast Asian Archive. “These are the folks who understand how powerful knowledge is, and have that sense of learning from others’ histories and experiences can only enrich your own life and worldview. They harness that and are hopefully going to bring that into the classroom to their students – not to try to flatten out differences, but to coexist and thrive together.”

While the first day of the conference was online, day two brought educators from across Orange County to gather in-person at the UCI Student Center and enjoy a sense of catharsis – both from being face-to-face and from finding a sense of community support after such a difficult two years.

“What really stuck with me was how healing the conference was, to me, and to many people,” says Fuko Kiyama, a School of Education Ph.D. student who coordinated the conference volunteers.

|

“It’s essential for teachers to not only teach social movements of specific ethnic groups in California, but also to create classroom communities where students can see themselves as active change agents in their local communities.” – Nicole Gilbertson, director of the UCI Teacher Academy and the UCI History Project |

“There were a lot of tears because it felt like such a safe and loving atmosphere.”

Throughout the event, participants were asked to pause for a moment and dedicate their learning to someone – an ancestor, a parent who sacrificed to immigrate, or even their childhood selves, who needed to feel seen. “I wish I had this when I was a student growing up in Southern California,” says Yung in the conference’s opening session. |

Ethnic studies curriculum

Soon, all public K-12 students in California will take an ethnic studies class. With the passage of Assembly Bill 101, which Gov. Gavin Newsom signed into law in October 2021, high schools will be required to offer a semester-long course in ethnic studies beginning in 2025-26. Already, educators are working on curriculum and professional development programs to prepare educators to teach these new classes.

“For 20 years, I’ve been a believer in ethnic studies, but just in the past two years we’ve seen real movement around getting ethnic studies into the K-12 curriculum,” says Vo Dang. “It’s not new, but a lot of the current teachers left college before Asian American, African American and Chicano/Latina studies became part of the higher education landscape, and so they don’t really know how to talk about these concepts.”

Vo Dang and UCI colleagues believe that incorporating local voices and perspectives will be critical to the success of ethnic studies programs.

“It’s essential for teachers to not only teach social movements of specific ethnic groups in California, but also to create classroom communities where students can see themselves as active change agents in their local communities,” says Gilbertson.

As a large producer of Asian American educators in the region, UCI plays a special role in equipping teachers with the tools and resources to incorporate culturally relevant materials in their classrooms, and Asian American stories in particular.

Gilbertson is working with Vo Dang, the co-author of A People’s Guide to Orange County (UC Press, 2022) and the organization that Yung and Nguyen established, Educate to Empower, to provide resources for effective ethnic studies curricula in local classrooms. Yung and Nguyen have offered workshops through the UCI Teacher Academy since 2021 that focus on topics such as the anti-racist classroom, stopping AAPI hate, and creating affinity spaces for local educators of color.

“Because it’s UCI, because it’s a research university, and because of the people we have on the team, this was a real opportunity to create a community of educators made up of alumni of teachers,” says Gilbertson. “There was this emotional aspect of coming together and sharing stories at the conference that forged a sense of community, and that’s something UCI can continue to facilitate.”

Ninety percent of survey participants said they acquired new knowledge and skills during the conference. Organizers assembled robust curriculum resources based on the sessions to provide attendees, and they are actively working on ways to continue supporting the burgeoning community of local educators who want to weave Asian American studies into their classrooms.

“Well beyond just bringing resources, we built community from this conference,” says Vo Dang. “This is UCI’s responsibility regionally – not just to our own students and faculty, but to our larger community.”

Soon, all public K-12 students in California will take an ethnic studies class. With the passage of Assembly Bill 101, which Gov. Gavin Newsom signed into law in October 2021, high schools will be required to offer a semester-long course in ethnic studies beginning in 2025-26. Already, educators are working on curriculum and professional development programs to prepare educators to teach these new classes.

“For 20 years, I’ve been a believer in ethnic studies, but just in the past two years we’ve seen real movement around getting ethnic studies into the K-12 curriculum,” says Vo Dang. “It’s not new, but a lot of the current teachers left college before Asian American, African American and Chicano/Latina studies became part of the higher education landscape, and so they don’t really know how to talk about these concepts.”

Vo Dang and UCI colleagues believe that incorporating local voices and perspectives will be critical to the success of ethnic studies programs.

“It’s essential for teachers to not only teach social movements of specific ethnic groups in California, but also to create classroom communities where students can see themselves as active change agents in their local communities,” says Gilbertson.

As a large producer of Asian American educators in the region, UCI plays a special role in equipping teachers with the tools and resources to incorporate culturally relevant materials in their classrooms, and Asian American stories in particular.

Gilbertson is working with Vo Dang, the co-author of A People’s Guide to Orange County (UC Press, 2022) and the organization that Yung and Nguyen established, Educate to Empower, to provide resources for effective ethnic studies curricula in local classrooms. Yung and Nguyen have offered workshops through the UCI Teacher Academy since 2021 that focus on topics such as the anti-racist classroom, stopping AAPI hate, and creating affinity spaces for local educators of color.

“Because it’s UCI, because it’s a research university, and because of the people we have on the team, this was a real opportunity to create a community of educators made up of alumni of teachers,” says Gilbertson. “There was this emotional aspect of coming together and sharing stories at the conference that forged a sense of community, and that’s something UCI can continue to facilitate.”

Ninety percent of survey participants said they acquired new knowledge and skills during the conference. Organizers assembled robust curriculum resources based on the sessions to provide attendees, and they are actively working on ways to continue supporting the burgeoning community of local educators who want to weave Asian American studies into their classrooms.

“Well beyond just bringing resources, we built community from this conference,” says Vo Dang. “This is UCI’s responsibility regionally – not just to our own students and faculty, but to our larger community.”

Conference organizers, from left, Mary Nguyen, undergraduate; Thuy Vo Dang, curator, Southeast Asian Archive; Stephanie Reyes-Tuccio, director, Center for Educational Partnerships; Fuko Kiyama, graduate student; Tuyen Tran, assistant director, California History-Social Science Project; Wenli Jen, founding president, School of Education Alumni Chapter; Naehee Kwun, UCI Teacher Network Facilitator; Jeff Kim, teacher, Anaheim Union High School District; Nicole Gilbertson, director, UCI Teacher Academy and UCI History Project; Stacy Yung and Virginia Nguyen, co-founders of Educate to Empower. (Not pictured: Judy Wu, professor of history and Asian American studies)